JANUARY 17, 1968.

At the Trocadero in Sydney, temporarily concealed by chintzy cliffs of gold nylon, was Elvis’ gold Cadillac. The 1960 Series Fleetwood 75 Limousine—bought for $10,000 US and with $65,000 of modifications—was touring Australia in place of its owner. Even the tour-weary Beatles thought the idea was genius. At a time when his mass appeal was waning, Elvis toured a proxy that in its gold plating, it’s full compliment of household items and 40 coats of “crushed diamonds and fish scales from the orient”, fully encapsulated the magnificence of Elvis’ legacy. An American monument touring an American monument—and a reminder to everyone that he was still the King.

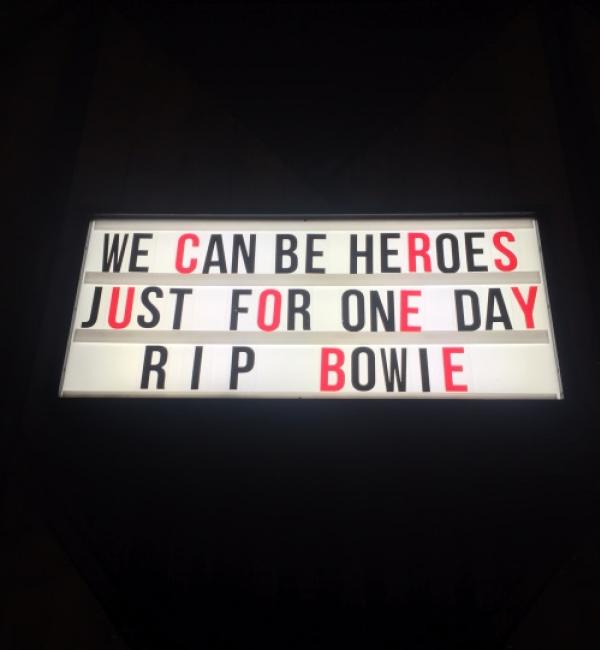

David Bowie hasn’t even needed to suffer a decline to start touring his possessions. Or to remind people how much they love him. The V and A Museum’s David Bowie Is exhibition has swarmed around the globe, tapping into a perennially present adulation for Bowie. A red and blue lightning bolt is enough to confer instant meaning onto people from three different generations. Advertisements proclaiming “David Bowie Is Coming To Town…Beep Beep” are pasted over the noses of trams, an approximation of the Lyrics to ‘Fashion’—no need for contextualization. David Bowie Is doesn’t feel like a retrospective of just one man’s musical morphology. It feels more like a yellow brick road through 20th Century culture—a series of guided collisions, steered by a narrator who continues to transfigure, always just beyond our reach.

JULY 15, 2015. 1:15PM.

There’s four lightning bolts arranged into a small storm above the Media Communications preview, suspended over a crowd of people whose careers appear to dine frequently on the rest of their lives. Mostly everyone looks tired, simulating relaxation from behind flutes of Mot. Four more iconic Philo/Duffy/Bowie-designed lightning bolts are deployed over the glass and Perspex of the ACMI Lightwell. KW and I creep over to the subterranean marble throat of the exhibition entry and are instantly mistaken for fans and warmly encouraged to return the next day. We gesture towards the champagne pen and are warmly encouraged to return there, instead. KW is my cultural confidante (loves the living shit out of David Bowie) and is in enthusiastic tow as a kind of bipedal Bowie encyclopedia.

[AUTHOR’S NOTE: For Some Context: on the way to the exhibition, 2 quotes.

1. KW: “I’m not exactly sure how old [Bowie] is…I know he’s 2 years older than my Dad..”

2. KW: “I decided not to wear my glasses because I don’t want any separation between myself and his Glory”]

The bank of bodies under the damoclean lightning bolts seems more underwhelmed and underslept as time draws on—like the whole thing is some kind of low-grade toil. I bear witness to the phrases: “but I have to learn to take some time out” “I have to make some time for perks” and “the emails are piling up” — all before the courtly pre- exhibition speech has even begun. Then afterwards, following some bovine shuffling away (sadly) from the champagne table, and some carefully dispensed instruction on how not to touch our audio guides, we’re inside.

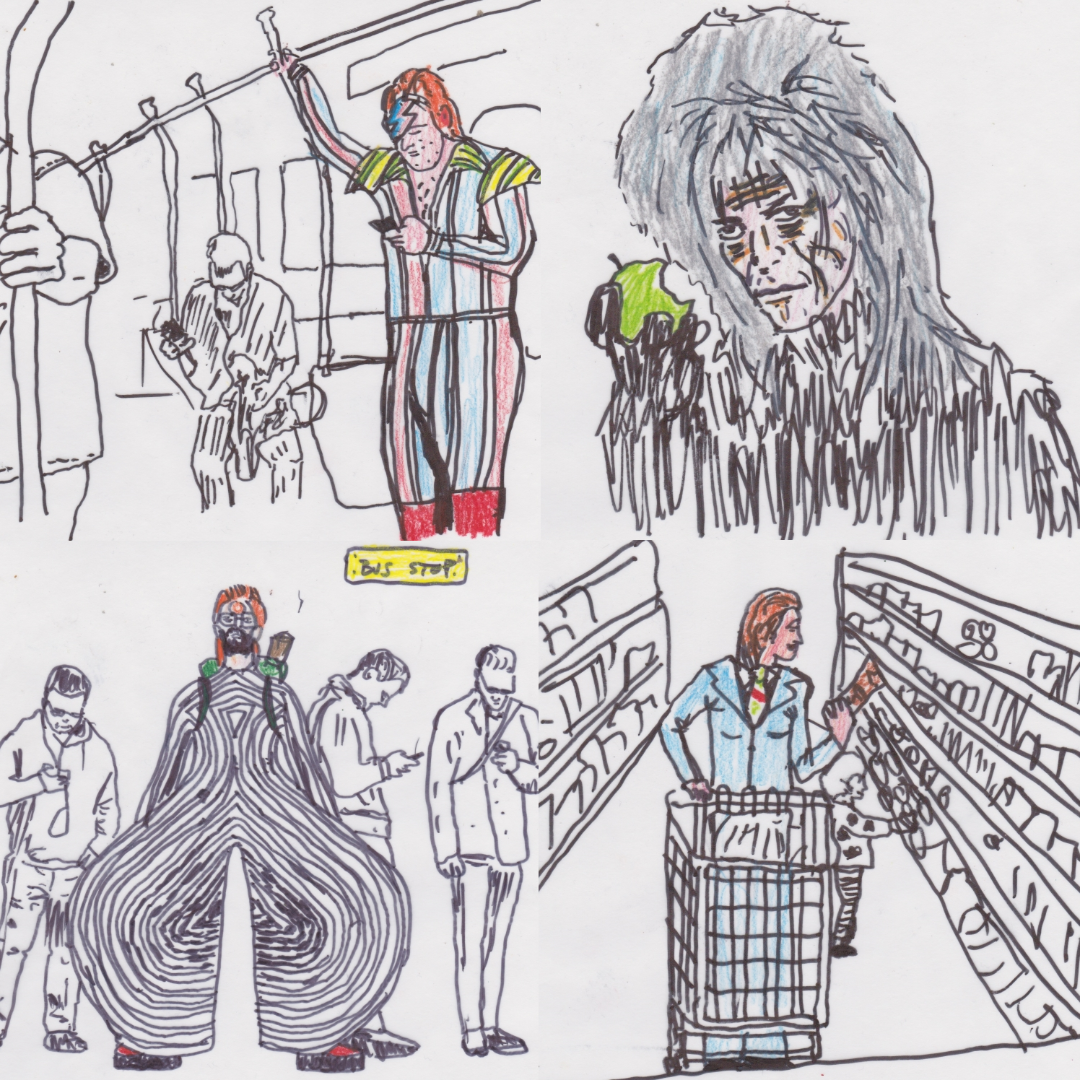

The exhibition is small string of (for the most part) chronologically adorned antechambers. One exception is the first display—a kind of visual abstract for the show—an Aladdin Sane-era Kansai Yamamoto-designed bodysuit, featuring massive zeppelinesque legs, and concentric white stripes sewn over black vinyl. The overall effect is one of mesmeric audacity—(imagine if Salvadore Dali found a career re-striping traffic lanes). And it only gets more flamboyant from here. There are knitted jumpsuits pulled over corporeally posed mannequins, Bowie’s personal cocaine spoon and sketches for the huge sets on Diamond Dogs tour—scrawled like a monstrous dystopian city. There is footage of Bowie’s ‘Verbasizer’, his random word generator from 1997, akin, he claims to “creat[ing] images from a dream state.” Despite the leaping tapestry of ideas, gushing audially and visually from the exhibition with near-overwhelming magnitude and detail, the Media and Communications crowd move at a speed that seems only barely slower than the speed of regular human transit. Occasionally small groups instinctively wad together like small, semi-professional dams in the racing tide of bodies. It’s unclear if the crowd’s sensible expedience—a kind of ambling disinterest—is just the effect of looking at any crowd from a distance. But what is clear is the palpable lack of fascination in the room’s bodies. But this could be a symptom of the subject as much as the audience. Bowie—such an instantly recognizable icon of music, fashion and wider popular culture—is now one of modern music’s totems. He’s omniscient—normalized. Some of the exhibition’s Ziggy-era news footage reminds us of his more iconoclastic heritage: “An ex-arts student from Brixton…turned himself into a bizarre, self-constructed freak.” Likewise in his book Ziggyology, Simon Goddard talks about Bowie as possessing an “infinite mystique of bewitching otherness.” But being such a landmark, (much like Dylan or the Beatles before him) Bowie is now an axis from which musical comparisons swing, a designation that despite its prestige, forgets how radical he truly was. David Bowie Is serves as a kaleidoscopic reminder of something truly other.

JULY 16, 2015. 6AM.

The city’s brownish dark is bleeding neon, it’s streets blurred with wind. There’s a line of people unfurling from ACMI’s glass doors through a cordoned race and along the side of the building. It’s fiercely cold, but nobody seems to mind—this is a special sort of crowd. Quiet, determined and impervious to weather, insulated by what surely must be a near-clinical grade of obsession. It’s the morning of the exhibition’s opening, but people here are not queuing in the dark for Bowie himself, or even to be some of the first members of the general public through the exhibition doors. They’re waiting for the gift shop to open. And due to the projected demand, the gift shop is opening at an especially early 7:30am. The objects in demand are: a Melbourne-only, yellow-disc vinyl of Bowie’s1984 single ‘Let’s Dance’ and a limited vinyl edition of his intimate 2008 compilation ‘iSELECT’. There are 500 copies of both, a number that by 8am, the growing, snaking line will have undoubtedly devoured.

[AUTHOR’S NOTE: And it does. The cashier informs me that this is, by a long margin, the biggest queue for the gift shop that ACMI had ever encountered. It rivals the actual entrance queue on the opening of the Tim Burton exhibition, apparently.]

There’s a very particular fervor that attends Bowie fans. It’s this fervor that has drawn a slightly portly Ziggy Stardust out of bed, poured him into a powder blue suit and conveyed him at 5:30am to the front of the queue at the ACMI doors. It’s this fervor that has convinced a weathered older father to bundle his small children into coat and pram before cocooning himself in his New York Yankees jacket and shambling towards the city and into the line in front of me.

[AUTHOR’S NOTE: A really good on-the-ground-case-in-point for this fervor is the ‘Stardom and Celebrity of David Bowie’ Symposium that is running concurrently with the first week of the exhibition. Even with Bowie not attending the lectures in any way, the ticket price is still $150 and is tipped to sell out. Another more recent example is the case of Professor Will Brooker from England’s Kingston University who just this week announced that he’ll be dressing and method acting various Bowie personas for a full year “in an effort to better understand the elusive rock star.”]

This fervor seems driven by more than music or fashion. What Bowie seems to offer is closer to a way to live— the possibility of transcendence, from Brixton arts student to Starman, from the everyday to something wondrous. The allure of otherness.

“Train was already packed coming in” someone yawns behind me “people looked depressed.” Even here, the promise of something ‘other’ is quietly present—quite unlike the same rain-streaked beginnings of morning that sluice through the rest of the city. There’s an impossibly fresh ACMI staff member weaving through the line, taking coffee orders, there’s a New Years Eve-style countdown to the shop’s opening at 7:30 and boisterous cheering and applause as the first customers buy their records (Staff, it should be pointed out, are very into this, instigating both the cheers and the preceding countdown.) It’s all very clever. The limited edition Melbourne-only disc naturally provokes the idea of ‘owning a piece of Bowie’s history’—just the kind of inclusivity that helps in making him so magnetic. Bowie’s ability to penetrate and become inextricable from people’s personal worlds is part of what drives his mystique; his ‘otherness’ isn’t something wholly distant, but something close to inspirational. He really is what Mainman Marketing policy suggested during his Ziggy years—a Man who became a Starman. And devout fans end up begging the same question that fill some of his (on display) early promotional posters: “Can a Young Man…Find Happiness as a Starman?”

But the membrane between myth and reality seems permeable from both directions. Just as mania-drenched acolytes will take lines like: “I had to phone someone so I picked on you” as a barely coded instruction to cut Bowie a copy of the key to your skull, they equally desire a long glimpse of the flesh behind the myth. David Bowie Is assents, displaying, among costumes and lyric sheets, personal details and accouterments. There’s a loop of medieval-looking keys from Bowie’s apartment in Berlin. There’s his personal measurements: “chest 34, waist 25, seat 25, wrist 8, thigh 19, biceps 11.” There’s childhood photos, Bowie’s (or Davy Jones’) features spread wide over the real estate of his young face. There’s demystifying quotes like: “He absorbs Brecht, cabaret, expressionist art, European fashion [as well as] beer and sausages.” There’s the aforementioned Thin White Duke-era cocaine spoon. These are, of course, perfectly placed in the exhibition, and help us travel like baggage under his spidery arm, a microcosmic version of the voyage some fans began over 40 years ago.

According to David Bowie Is, David Bowie is:

Watching You

Someone Else

Saying You’re Wonderful Give Me Your Hands

All Around You (near exit – words impaled by length of black gaffa tape)

All Yours

Imagining a City

Graphically Yours

Getting Ready For His Close Up (Outside the portable photobooth)

From Berlin

Saying the Shame is On the Other Side

Quite Sure of What He’s Going Through

Moving

Moving Like a Tiger On Vaseline

Wearing Many Masks

Crossing the Border

Looking For a Future That Will Never Come To Pass

A Face in the Crowd (On tote bag)

Making Himself At Home (promo design on the wall of the ACMI cafe)

David Bowie’s Best Known Alternate Personas:

Ziggy Stardust

Major Tom

Aladdin Sane

The Thin White Duke

The Minotaur

Detective Nathan Adler

A Few of David Bowie’s Early Stage Names/Band Names:

Dave Day

Alexis Jay

Luther Jay

Davey Jones

Davey Jones and the King Bees

Davey Jones and the Konrads

Davey Jones and the Bowmen

Assorted Quotes, Roles and Anecdotes from Bowie Is That Seem In Some Way Mimetic For Bowie’s Cultural Impact

1. “All art is unstable—it’s meaning is not necessarily that implied by the author. There is no authoritative voice, only multiple readings.” – D.B.

2. “Living is one big sculpture” – Gilbert and George.

3a. “But they made their mark because eventually I’d end up reading them.” – A young D.B. on reading lofty books to look smart.

3b. “I know it might be impossible for you to attend but…” – The earnest note from lauded English author Christopher Isherwood to Bowie, inviting him to attend a party while they were both living in Berlin.

- “I didn’t know whether I’d find God as a Buddhist or I wanted to be a rock and roll star” – D.B.

- David Bowie’s undertaking of Brecht’s Baal, his character a tramp that haunts high society.

- Some of the guests in attendance at the opening night of the Aladdin Sane tour: Bette Midler, Andy Warhol, Allen Ginsberg and Salvadore Dali.

JULY 18, 2015. 11AM.

The crowd on the first weekend of David Bowie Is has the lopsided, shuddering motion of a broken carousel or an overburdened truck. The people here are—both in volume and demographic variety—the greatest I’ve seen all week. Mothers and fathers beat slow paths with prams—faces like grey waterfalls of fatigue. There are quiet explosions of childhood awe—which, incidentally, look identical to ageing suburban recollection. And there’s still a large enough representation of the 20s bracket that if the room’s collective septum piercings were harvested and melted down, there’d be enough material to make a life-sized Ziggy Stardust bust with molten aluminum to spare. There’s a kind of funhouse mirror-effect in audience and artifact—the crowd functioning as an unwitting, deformed reflection of the exhibition’s own diffuse nature. It remains one of the enduringly tantalizing fascinations that swirl around Bowie—his bewildering diversity as an artist. And more pointedly, how he manages to shapeshift in a way that seems immune to artificiality. Bowie Is guides us through all of his (ch-ch-ch-ch) changes. It’s at once Kabuki theatre, a sexually deranged dystopia, a psychedelic odyssey aimed at the heavens, a monochromatic cabaret and a thrumming dance club. It’s an intersection of Japanese fashion, German Avant-garde, American Rock and Roll and English aplomb, a cosmic mixture of Iggy Pop, Stanley Kubrick, Charles Mingus, Alexander McQueen and Bob Dylan. A zone of gradual flux, where Anthony Burgess, George Orwell, Bertold Brecht and Williams Burroughs can all be on the same page. His chameleonic career is so captivating that people have forged academic careers on the back of its analysis. Such a person is Tanja Stark, whose monolithic essay ‘Crashing With Sylvain: David Bowie, Carl Jung and the Unconscious’, details exactly how Bowie’s career and masks resonate with Jung’s various archetypes. She’s now a kind of go-to Bowie/Jung scholar and is speaking at the $150 seminar.

After my third exit from ACMI for the week, a thought settles. I’ve spent a week trying to manufacture something intimate between Major Tom and myself and repeatedly noticing that I always feel most enamored just as I’m leaving. Not as I’m being drenched by the iconic words pouring through my headset or transfixed by some cartographically undulating garment. I genuinely feel in some remote way, transported. This seems to be what Bowie Is most effectively distills—how his strange and various mutations, rather than push people away, draw people towards the alien and the other—in some small way out of themselves. This seems to be the real reason for Bowie’s enduring adulation. He’s didn’t just fall to earth. He took us with him when he left.

- Paul Cumming aka Wax Volcanic for Cool Accidents